The following entry was submitted by Morgan Baumgartner, a student from the University of New Hampshire majoring in Biomedical Sciences – Medical Microbiology.

Written by Morgan Baumgartner

Debilitating. Prevalent. Preventable. Neglected. One of these words is not like the other. Why would diseases that can be described by the first three terms also be described by the last? Why should infections that inflict millions of people globally be ignored by the majority of the world? Is it because these diseases inflict only the poor, the forgotten, and those that have been swept under the rug? There are an infinite number of diseases that may be cured if more fortunate people did not turn a blind eye to the suffering of their less wealthy brothers and sisters. Although these ailments may seem to overwhelm poorer areas of the world, global cooperation, compassion, and commitment to helping others can help shed light upon and eradicate neglected tropical diseases.

- Neglected Tropical Diseases: An Overview

“It is a trite saying that one half of the world knows not how the other half lives. Who can say what sores might be healed, what hurts solved, were the doings of each half of the world’s inhabitants understood and appreciated by the other?” – Mahatma Gandhi

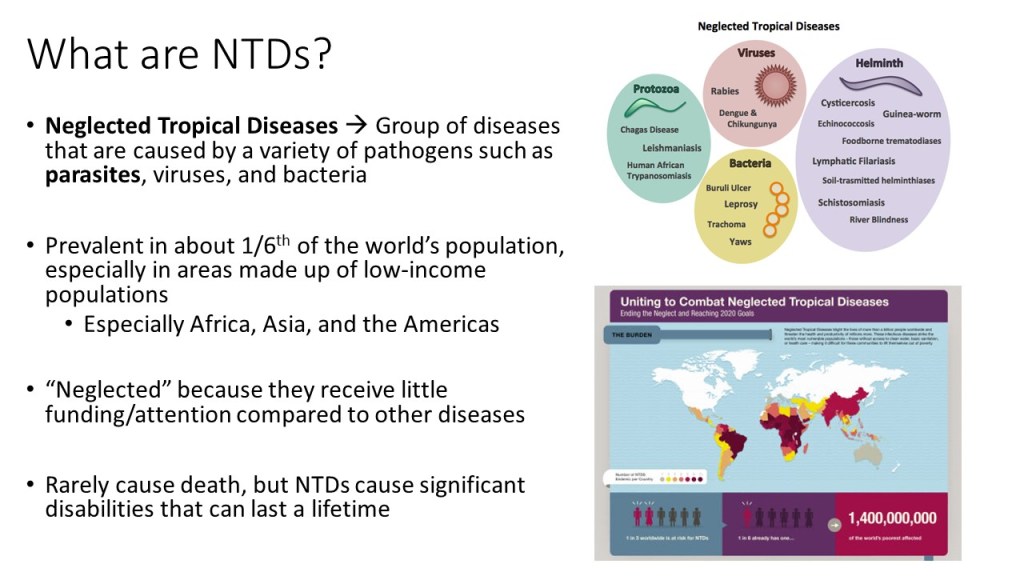

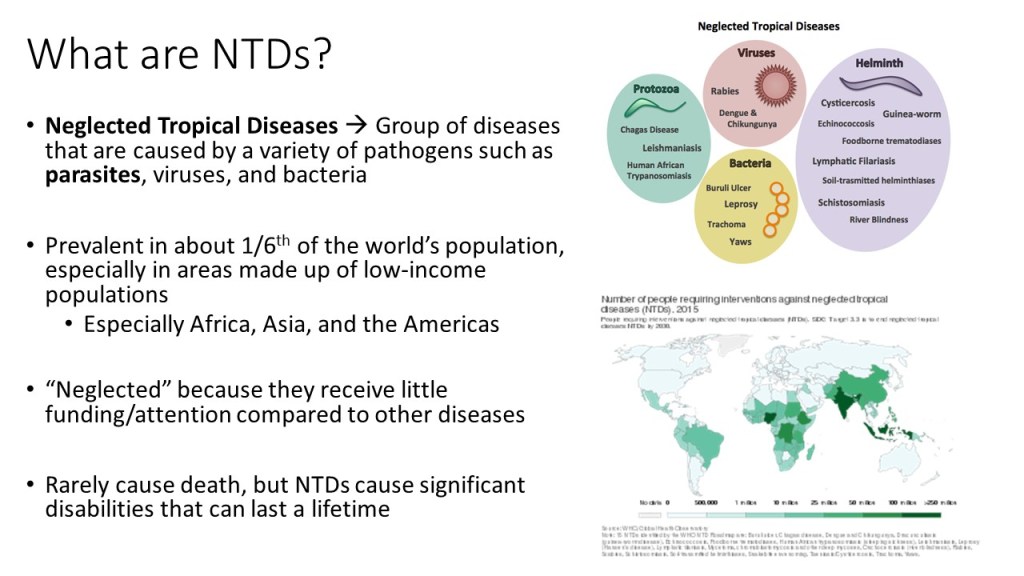

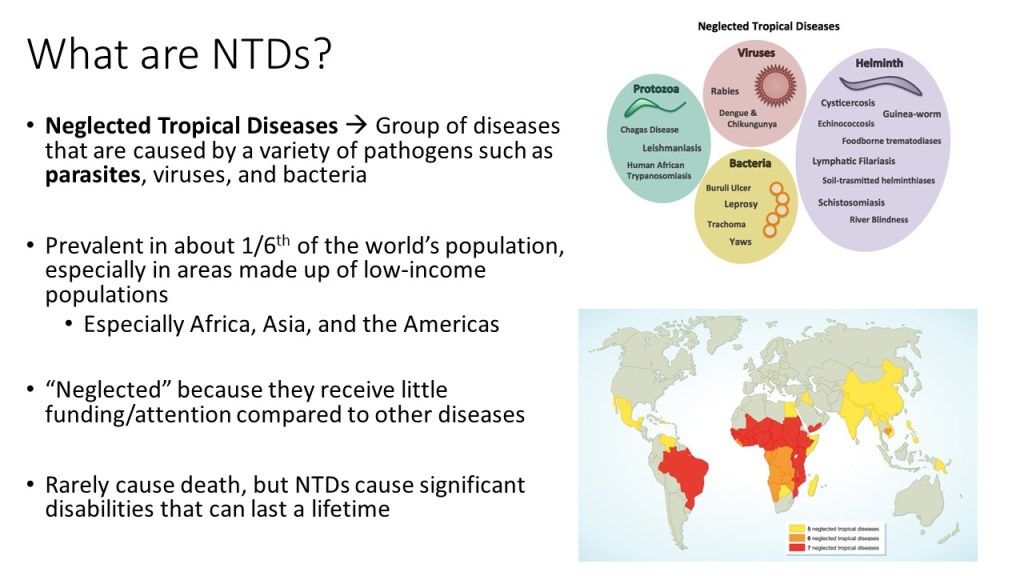

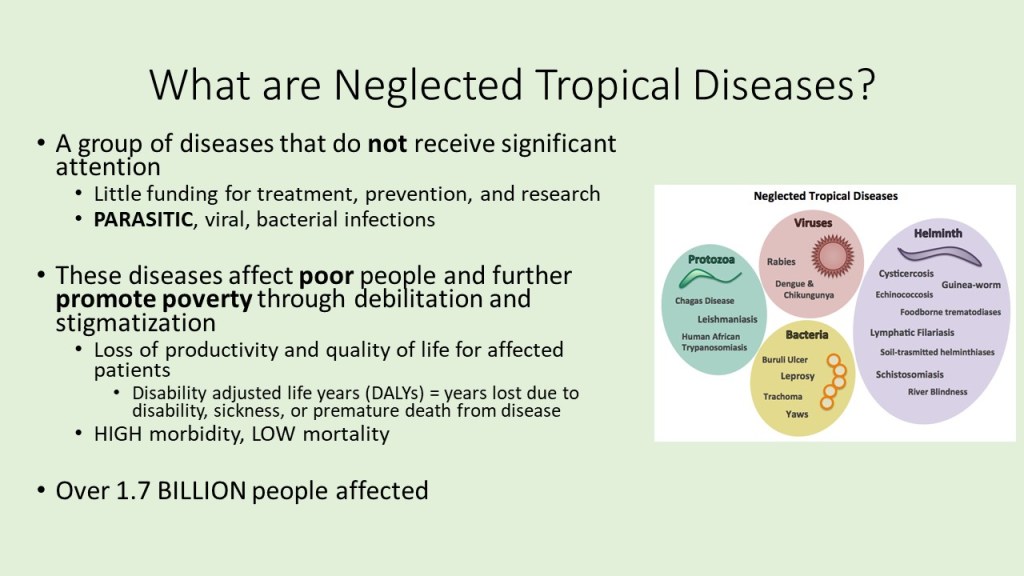

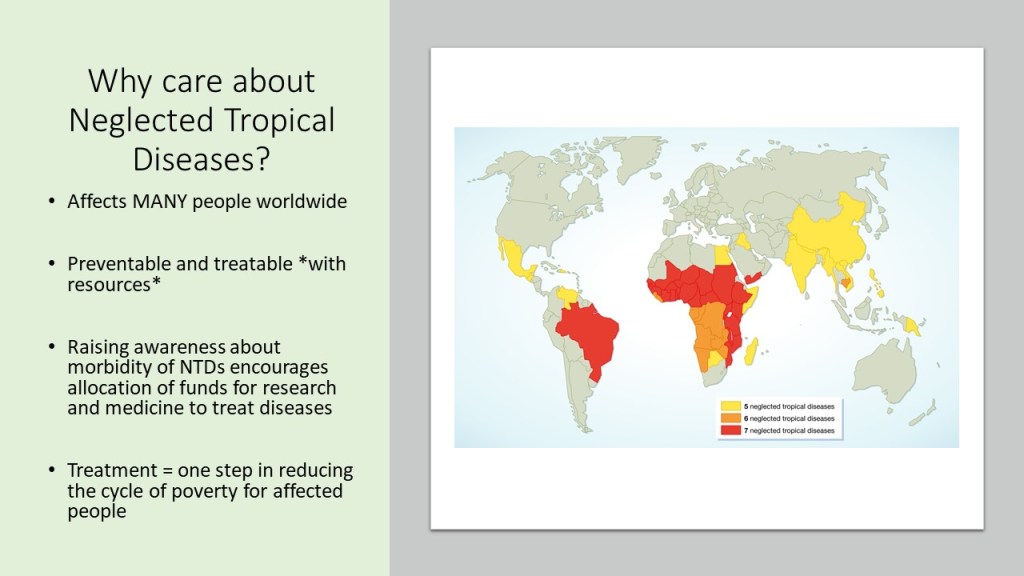

Neglected tropical diseases, or NTDs, are not the typical diseases that the everyday person hears about on the news. They are classified as a group of communicable infections that are common in tropical and subtropical regions (WHO, “NTDs”). More than one billion people are inflicted globally and these diseases are primarily found among impoverished people living in rural communities of developing countries. Worldwide, 149 different countries are affected by at least one NTD, with many countries harboring seven or more NTDs endemically (CDC, “NTDs”). Since these infections are common among the poorest of the poor and are out of sight and out of mind, NTDs are not given the proper attention by governments and global agencies that they need. Thanks to the help of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, The Carter Center, George Clooney, Oprah Winfrey, and other big names, however, the NTDs have received the global publicity required to address the problems that they are causing in the world’s poorest people.

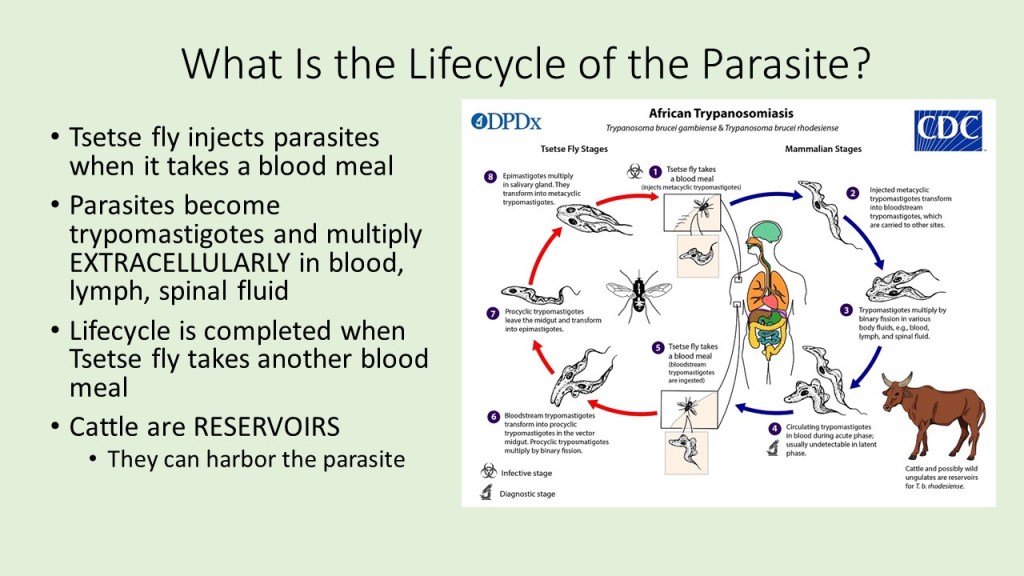

Since 2005, the World Health Organization has identified seventeen of the most prevalent, core NTDs. These are classified by their causative agent, how and where the disease develops, and where they are most commonly found. The core NTDs are split into four major groups based off the agent of disease: helminth (worm) infections, protozoan infections, bacterial infections, and viral infections. The helminth infections are further divided into soil-transmitted helminth infections and other helminth infections, which include transmission by snails, water, and food. Within each of the broad classifications, there are groupings of each organism by pathogenesis, as well. For example, helminth infections include a subclass of filarial infections, which cause disease in the blood and lymph. Examples of these infections include Wuchereria bancrofti, a causative agent of elephantiasis via mosquito, and Onchocerca volvulus, the causative agent of River blindness via blackfly. Although these pathogens are both parasitic worms, they infect humans with different vectors and cause separate diseases in dissimilar areas of the body. The many ways that the NTDs can cause infection and their varying life cycles make it important for study and classification of each one to be established.

The NTDs can also be differentiated by where they are most commonly found. For example, Leishmaniasis, which is caused by protozoan Leishmania spp., can be diagnosed based on where in the world the infection is found. Leishmania tropica, for example, is most commonly found in the Middle East and South America, causing cutaneous lesions. Knowing the demographic of this disease helps differentiate which cutaneous NTD is causing a patient’s symptoms. Leismania brazilienses, on the other hand, causes mucocutaneous infection in Brazil and surrounding countries and Leishmania donovani causes visceral leishmaniasis in Sudan, Inda, and Nepal, which is a way that these three species can be distinguished (Bessat). Another example of differentiation by global distribution is with Hookworm infections, which are a type of soil-transmitted helminth infection. The two Hookworm species are Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale. Both worms and their eggs look almost identical under light microscopy of fecal samples, therefore making them hard to differentiate (Hawdon). However, N. americanus is prevalent in the “New World”, or the Americas, whereas A. duodenale is more commonly found in Africa, or the “Old World.” Knowing where the NTDs are commonly found is a helpful categorization tool that is used for epidemiological tracking and diagnosis of disease.

Although the NTDs are all different and can be classified by varying means and modes of infection, there are many overlying characteristics that they share. The eight major attributes that all NTDs possess are: high prevalence, linkage to poverty and rural areas, non-emergent diseases, causes chronic conditions, source of disability and loss of healthy life years, low in mortality, ostracizing, and poverty-promoting. The symptoms of NTDs cause developmental problems in humans, ranging from mental and physical disabilities in children to debilitating deformities in adults (Hotez). This perpetuates the vicious cycle of poverty by decreasing access to education and healthcare in already disadvantages people, preventing them from making better lives for themselves and their families. The physical and economic impacts all NTDs share make it pertinent for the global community to take a stand and fight to end the burden of disease on the billions of infected people.

- High in Morbidity, Low in Mortality

“A civilization is judged by the treatment of its minorities” – Mahatma Gandhi

As discussed previously, NTDs affect many people around the world, especially those in poorer countries. These NTDs are chronic diseases that cause disability and disfigurement, thus inhibiting many people from making lives for themselves and removing themselves from the impoverished areas that they live. For example, filarial elephantiasis caused by W. bancrofti and Brugia malayi leads to debilitating chronic disease in an estimated 40 million people in over 39 endemic countries (Yimer). It is considered as one of the most disabling diseases that effects mostly poor and marginalized people, causing permanent damage in the lower extremities (Yimer). Infected individuals experience extreme edema, painful lymphadenopathy, and restricted ability to use their legs due to swelling (Yimer). Not only does this disease affect people physically, but it causes them to be ostracized from their families and friends, lose job opportunities, and leads them to resort to begging on the streets. However, it does not cause death in the individual immediately, resulting in a chronic disease that decreases any infected persons’ quality of life greatly.

The case of filarial elephantiasis is not alone in its physical and socioeconomic impact. Hookworm infections, which have a prevalence of around 600-700 million cases, cause associated iron-deficiency in 146 million individuals with the disease (Bartsch). The effects of anemia are well known in both children and adults – motor and cognitive delays, pregnancy complications, depression, heart problems, and increased risk of infection due to immunosuppression from the disease (NIH). Chronic schistosomiasis, which is a urogenital and intestinal disease caused by Schistosoma spp., is associated with anemia, poor school performance, reduced productivity, and malnutrition and growth impairments. Onchocerciasis, caused by O. volvulus, is a disease that produces a serious stigmatizing skin disease as well as visual impairment and blindness in approximately 800-thousand people.

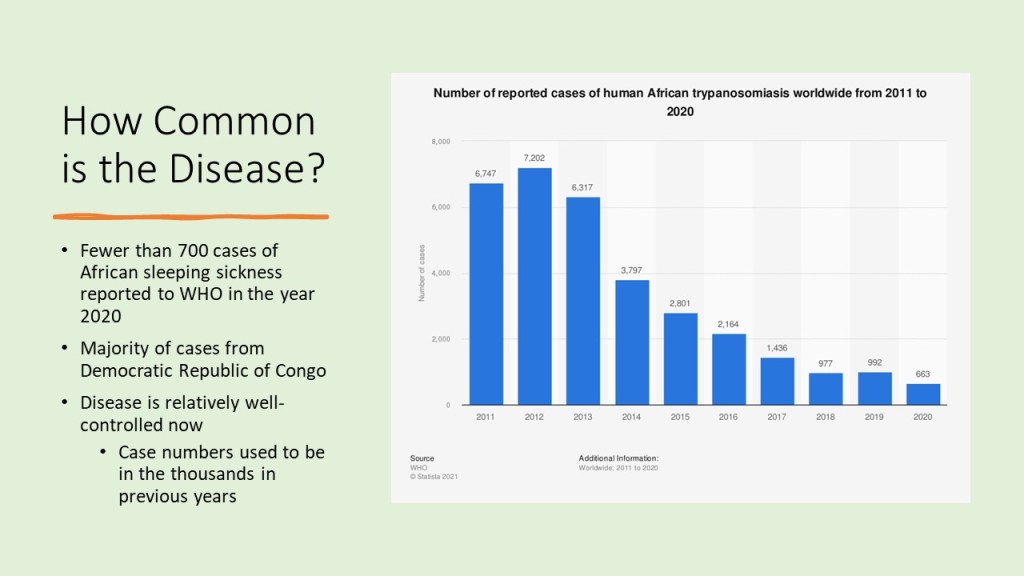

Although billions of people are affected by NTDs, only approximately 530-thousand individuals die annually of any complications related to their infections. This leads to less of a focus on the NTDs because people are not actively dying. However, this does not mean they are not being effected negatively. The disability-adjusted life years, or DALYs, consider the number of healthy years lost from premature death or disability due to disease. NTDs are estimated to have 56.6 million DALYs annually, despite having such a low mortality rate. Filarial elephantiasis causes 2.8 million DALYs annually (GAHI), hookworm infections alone account for approximately 3.5 million of those DALYs (Bartsch), and schistosomiasis accounts for another 3.3 million DALYs itself (GAHI). Even though the number of DALYs caused by NTDs is more than the DALYs generated by tuberculosis and malaria, which are 34.7 and 46.5 million respectively, NTDs do not receive global attention due to their low mortality. Although not many lives are being lost as in the case of malaria and tuberculosis, NTDs take away many healthy, livable years from infected individuals that may help them get out of the cycle of poverty that they are trapped in.

- Learning by Example: Dracunculiasis and Yaws Eradication Efforts

“Medical science has proven time and again that when the resources are provided, great progress in the treatment, cure, and prevention of disease can occur.” – Michael J. Fox

As this quote above states, not all hope is lost when it comes to finding a way to stop the persistence of NTDs in impoverished nations. Two very successful cases involving the control and near eradication of NTDs are the multilateral work done by the Carter Center and other global organizations to help end Dracunculiasis and the World Health Organization strategy to eliminate Yaws.

Perhaps one of the greatest-known success stories is that of the near eradication of Dracunculis medinensis, the causative agent of dracunculiasis, otherwise known as Guinea Worm infection. In 1986, dracunculiasis affected more than 3.5 million people annually in over twenty countries across Africa and Asia (Carter Center). It is contracted through ingestion of water infected with copepods carrying D. medinensis roundworm larvae. Once inside of the intestine, the larvae mature and burrow their way into the skin of the lower extremities, where they cause an intense burning sensation and blister. To relieve discomfort, infected individuals place their leg in water, which releases the worm’s larvae into the water to begin the life cycle of the parasite again.

The traditional mode of treatment for Guinea Worm infection was by slowly pulling the roundworm from the lesion by wrapping it around a stick or piece of gauze. However, this treatment takes a long time, as the worms can grow up to a yard in length, and leaves individuals susceptible to secondary bacterial infections due to the open wound caused by the lesion. So, recognizing the need to help end dracunculiasis infection, the Carter Center in cooperation with WHO, UNICEF, and the CDC, helped develop a plan that would stop transmission of the disease at the source. Since copepods are the reservoir for the roundworm larvae, programs were created to educate civilizations in endemic areas to filter all drinking water and avoid entering water sources if infected. Due to the multilateral approach to the problem, extensive funding, and knowledge of the life cycle and mode of transmission of D. medinensis, Guinea Worm infection has been virtually eliminated, save the 30 cases reported in 2017 (Carter Center).

Another successful example of control of an NTD is in the case of yaws, otherwise known as endemic treponematoses. This disease is a chronic skin condition that affects young children, mostly between the ages of 6 and 10 and younger than 15 (WHO, “Yaws Eradication”). It is caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum subspecies pertenue, related species of which are the causative agents of syphilis. About 10% of cases result in gross disfigurement and subsequent social exclusion, which is why early detection and treatment of this disease is pertinent (“Yaws Eradication”). Yaws is spread by direct contact with fluid from skin lesions, which is why it is prevalent in humid, crowded, and impoverished areas that have poor hygiene (“Yaws Eradication”).

This disease was one of the first orders of business for WHO when it was first created in 1948, along with eradication of malaria. As such, it garnered widespread attention from the global community very quickly, allowing it to be addressed promptly and multilaterally. In the 1950s, there were approximately 100-150 million cases of yaws in 90 different countries (Kazadi). Since the agent of disease is a bacterium, it is easily treated by antibiotics. Originally, WHO ordered populations with over 10% of inhabitants infected with yaws to be treated with benzathine penicillin, and this seemed to work up until the end of the campaign in 1964. The prevalence of yaws decreased to 2.5 million cases, which was a 95% reduction, but attention no longer remained on the NTD after that. From the 1960 to the 1990s, there was no follow up with the control of the disease, and therefore the cases spiked back up to between 21 and 42 million in 2012 (Kazadi). In 2012, with a goal for eradication of yaws set for 2020, WHO revamped their treatment strategy to a single dose of azithromycin that focused on total community treatment of any place where yaws was reported. The easy, inexpensive and single-dose treatment for yaws in the new eradication strategy has reduced the number of cases to 46 thousand in 2015 (WHO, “Yaws Factsheet”). Overall, the understanding of disease prevention and spread of these two NTDs, global outreach, and calculated approaches are what enabled them to be nearly eradicated from endemic areas.

- High Prevalence, But No Progress?

“Comprehensive, Africa-wide control of malaria and NTDs together would probably cost no more than $3 billion a year, or just two days of Pentagon spending. If each of the billion people in the rich world devoted the equivalent of one $3 coffee a year to the cause, several million children every year would be spared death and debility, and the world would be spared the grave risks when disease and despair run unchecked.” – Jeffrey Sachs

Unfortunately, we do not live in a perfect world where everyone is willing to do the selfless thing to help the less fortunate. The above quote by Jeffrey Sachs, the chair of the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health, highlights how “easy” it would be to eradicate and properly address NTDs if everyone with money cared a little bit more about them. Being an extremely wealthy man himself, he understands how much power the elite have in making a change; but the incentive of being a good person is not enough to spark global cooperation among the wealthy. Instead, international organizations, such as WHO and UNICEF, must rely on the good will of individuals that want to make a difference. Sadly, that means that there is not always enough funding for research on these organisms, their life cycles, and methods to treat them.

Additionally, many international bodies consider HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria the more important targets for eradication as they have a higher mortality rate. Furthermore, NTDs are stigmatized and associated with poverty and lack of hygiene. Since many wealthy, capital cities do not see the silent effects of NTDs, many governing bodies would rather look the other way than help, as discussed above. The most highly affected areas are found in low- and middle-income countries that are still developing, which do not have the proper resources to get their infrastructure on stable ground let along treat endemic, chronic diseases. This explains why the majority of Northern American and European countries are not afflicted by NTDs, as they have the proper healthcare, sanitation, and civil systems to prevent the spread of these types of communicable diseases.

Another reason why there has not been significant progress in the control of NTDs is the variation in the mode of transmission. A large factor in why the two diseases discussed above are able to be effectively prevented is due to the simple way in which they are spread. In the case of Guinea Worm, copepod carriers are easily filtered out of drinking water with factory-made or home-engineered filters. The causative agent of yaws, T. pallidum, is easily treated with a one-time dose of antibiotic that has a long shelf life and is inexpensive to produce. Organisms that have been well-studied and impact people other than impoverished individuals gather more attention and eradication than others.

Alas, not every mechanism of infection is as simple as the above two examples. NTDs with arthropod vectors, for example, such as Chagas disease, leishmaniasis, onchocerciasis, and West Nile Virus, are especially hard to prevent. Trying to implement vector control is not only costly and low in effectiveness, it also has long-lasting and debilitating effects on humans and the environment. This has been noted in the attempted eradication of malaria, as bed nets are only minimally effective and use of insecticides, like the toxic but effective DDT, has harmful side effects on surrounding areas and people. On another note, some NTDs are transmitted through traditional practices or lifestyles that are engrained into the daily routines of villages and civilizations. An example of this is with hookworm infection, which infects people by burrowing into the skin of the feet and lower extremities. Many communities in Africa and Asia do not practice wearing shoes or cannot afford to use them, so hookworm has easy access for infection. There are many reasons why more progress has not been made in NTD eradication, and, unfortunately, much of that comes from lack of funds, attention, and difficult means of prevention.

- Recommendations for the Future

“There are no better grounds on which we can meet other nations and demonstrate our own concern for peace and the betterment of mankind than in the common battle against disease.” – John Gardner

If we look at successful preventative and eradication efforts of the past, the most effective method in controlling NTDs is a multilateral approach that includes the efforts of numerous nations and international bodies. The 2020 roadmap for eradication of NTDs created by WHO and the CDC calls for 20 of the major NTDs to be exterminated in the next two years. If we as a global community are going to end NTDs within a reasonable amount of time, public health policies in endemic nations need to be revamped, research efforts to find vaccines and simple treatments need to be funded by major donors, NGOs, and pharmaceutical companies, and education about prevention for at-risk communities needs to be implemented.

In the case of schistosomiasis, a disease that effects up to 600 million people in developing countries, more efforts need to be taken to prevent maturation in snails. As snails are an intermediate host for Schistosoma spp., insecticides that effectively reduce snail populations without harming other freshwater life forms need to be researched. Since the cercariae of the organism does not cause disease by ingestion of contaminated water, rather by burrowing its way through the skin or mucous membranes, filtration methods like those used for Guinea Worm infection would not be feasible (Inobaya). Rather, an effective way to determine if local waters used for swimming, bathing, or washing are infected with Schistosomes, like a nucleic acid amplification test of the water, would be an effective preventative measure that does not involve possibly harmful insecticides or treatments. Mass drug administration of Praziquantel, a safe, cheap, and effective treatment, should also be implemented in endemic areas, as reduction of the number of infected individuals also leads to the decrease in eggs produced. If the disease is addressed at the source, then it will eventually eradicate itself via natural processes.

Each NTD is explicitly unique and comes with its own set of obstacles to overcome. Some methods may work for the control of one NTD, but not another. It may be frustrating and goals that were set in previous years may not be reached in a timely manner. However, persistence is key with these kinds of infections. With global communication, commitment, and compassion for others, we can eradicate the diseases that affect over a billion people and make the world a better place.

Works Cited

Bartsch SM, Hotez PJ, Asti L, Zapf KM, Bottazzi ME, et al. “The Global Economic and Health Burden of Human Hookworm Infection.” PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 10(9): e0004922. (2016). Web.

Bessat M,Okpanma AC,Shanat ES. “Leishmaniasis: Epidemiology, Control and Future Perspectives with Special Emphasis on Egypt.” Journal of Tropical Diseases 2:153. (2015). Web.

Carter Center. “Guinea Worm Eradication Program.” (2018). Web.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Neglected Tropical Diseases.” (2018). Web.

Fox, Michael J. Commencement Address, Medical School Convocation, University of Miami (10 May 2003). From www.michaeljfox.org

Global Atlas of Helminth Infections (GAHI). “Global Burden.” (2018). Web.

Hawdon, John. “Differentiation between the Human Hookworms Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus Using PCR-RFLP.” The Journal of parasitology. 82. 642-7. (1996). Web.

Hotez, Peter J. “Impact of the Neglected Tropical Diseases on Human Development in the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation Nations.” PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 9(11): e0003782 (2015). Web.

Inobaya, Marianette T et al. “Prevention and Control of Schistosomiasis: A Current Perspective.” Research and reports in tropical medicine 2014.5 (2014): 65–75. PMC. Web. 10 May 2018.

National Institutes of Health. “Iron-Deficiency Anemia” (2018). Web.

World Health Organization (WHO). “Neglected Tropical Diseases.” (2018). Web.

— “Yaws Eradication.” (2017). Web.

— “Yaws Factsheet.” (2017). Web.

Yimer, Mulat, et al. “Epidemiology of elephantiasis with special emphasis on podoconiosis in Ethiopia: A literature review.” Journal of Vector Borne Diseases 2015.52 (2015). Web.